Conversation / Tommy Perman

Tommy Perman reflects on Scotland Can Make It! and his recent work across art, design and music.

In 2014 Panel launched Scotland Can Make It!, a series of six specially commissioned souvenirs for the XX Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, which included Great Circle, a souvenir app developed by experimental pop band and arts collective FOUND (Ziggy Campbell, Tommy Perman and Kevin Sim) in collaboration with Simon Kirby from the University of Edinburgh, design studio O Street, and the record label Chemikal Underground.

Scotland Can Make It! was part of the Glasgow 2014 Cultural Programme, aimed at engaging public audiences both across the city and internationally. The project set out to explore the notion of what a souvenir could be, connecting artists and designers with local industry and manufacturing to create a unique group of carefully developed ideas and objects that commemorated a particular time and place.

Ten years on, as Glasgow prepares again to host the XXIII Commonwealth Games in 2026, we speak to former FOUND member Tommy Perman about his involvement in the project and the motivations and inspirations behind his most recent work across art, design and music.

Great Circle pushed the boundaries of the traditional souvenir by creating a virtual audio-visual postcard of Glasgow. Can you tell us a little bit about your thinking behind the souvenir app?

From the very beginning of the FOUND collaboration we were interested in exploring artworks that evolved over time and changed depending on external influences. For Scotland Can Make It! we tried to think of ways to create a virtual artwork that could somehow be tied to the purpose-built Commonwealth Games Arena in the East End of Glasgow. Digital artworks can potentially be experienced simultaneously anywhere on the planet, so they have a different relationship to place than physical objects.

For the Great Circle app we made use of the geo-location tools available in smartphones. What you saw and heard in the app was determined by where you were in the world and by which direction you were travelling, in relation to the Commonwealth Games Arena. We wanted the interaction to be playful and to reward multiple uses of the app. As you moved closer to the East End, the music composition became fuller and the visual imagery became more detailed.

The Commonwealth Games was a time of significant change for Glasgow. I chose to draw images of two disused buildings that were awaiting demolition and two of the main spaces being developed for the Games. Users of the app would see these buildings being built or destroyed depending on whether they were travelling away from or towards the arena.

For the interactive musical composition, you used a sound technique called 'Convolution Reverb' to capture the unique sound within Glasgow’s Kelvinhall Sports Arena. How did this process connect to the development of the artwork in the app?

We created a ‘Convolution Reverb’ of Kelvinhall Sports Arena by making an audio recording of a starting pistol being fired in the space. The sharp loud sound of the starting pistol is made up of white noise – all the audible sound frequencies happening together at once. We recorded this sound and its echoes bouncing around the arena. We then imported the sound recording into specialist software which enabled us to play any instrument from our studio as though it was being performed inside Kelvinhall.

A ‘Convolution Reverb’ is a very accurate recording of the unique character of a space. In a similar way, the detailed drawings I made of locations in and around the Commonwealth Games Arena attempted to capture the unique character of those spaces.

The app itself functioned as a fragmented audio ‘postcard’ and could also be used to send a physical postcard from Glasgow. What role did the idea of the postcard play in communicating memories of place?

Postcards immediately came to mind when thinking about souvenirs. I’ve always loved sending and receiving postcards. They’re very accessible and affordable souvenirs. I find the format really charming and can’t help flicking through old postcards when I come across a box in a charity shop. Vintage postcards are highly nostalgic artefacts, tied to the memory of a place. In the era of social media, the physicality of a postcard really appeals to me. I enjoy the combination of an image on one side and a brief personal message on the other. I suppose there’s something quite playful in that the message on the reverse of the postcard isn’t hidden inside an envelope. The message can potentially be read by people while the postcard travels through the postal system but it’s not nearly as public as sharing messages on Twitter or Instagram.

Great Circle combined new digital technologies and traditional techniques and materials. How do these contrasting approaches influence your creative process, and does this combination often lead to unexpected or surprising outcomes?

I often search for ways to bring chance outcomes into my work. I enjoy combining processes and materials in ways that can lead me to unexpected results. This has frequently involved trying to fuse newer technologies with more conventional ones to see what will happen.

I’ve always had a dual interest in new and old technologies, and it feels natural to mix them up. I grew up with computers in my family home as my journalist parents were early adopters of desktop publishing. I was in my mid-teens when the internet started to become more accessible and I began making my own html pages soon after, exploring ways to share work online. Alongside this emerging digital tech my parents also developed their own black-and-white photos in a home darkroom, went to life drawing classes, made their own clothes, played in bands and sang in choirs. I can see how all these interests have influenced me.

Great Circle was created in response to a particular moment in Glasgow’s history. What do you think Great Circle would look like ten years on?

That’s a difficult question to answer. Physically the East End of Glasgow looks different now, as old buildings have been demolished, and new buildings built. So, if I were working on this project today, the locations I’d draw would likely have changed. I expect that people now have different relationships to interacting with apps and music, largely down to the huge influence of social media and streaming services like Spotify. I wonder how the ubiquity of social media would change the way people discovered the project too? I don’t know if we would manage to cut through the noise and reach people as it’s now so crowded online. However, I still think the ideas behind the project are interesting and there’s much more that could be explored with location-responsive artworks.

Collaboration forms the core of your practice. Can you tell us a little bit about why this is important to you?

Collaboration often leads me to unexpected and surprising results which I find refreshing. I learn so much through working with others and it’s such an important way for me to gain new perspectives.

I don’t believe in the myth of the successful individual artist who makes work in a vacuum. I know I wouldn’t have a career as an artist without the support of collaborators.

You have made a conscious decision to reduce the impact of your life and work in the environment. How does this influence your design process?

These days I try to ask myself if the thing I’m working on needs to exist at all. A lot of the time, I don’t think it really does. If I do decide to make something I try hard to research appropriate processes and materials that have the lowest possible negative impact on our environment. Instead of using new resources, I try to use equipment and materials I already have access to, borrow things or buy second hand. I like the creative challenge of working within sustainable limits.

If I didn’t have the pressure to earn money through making I expect my output would be much lower. I’m definitely a believer in slow working and my long-term goal is to produce less. Quite a long time ago I made the decision not to fly for environmental reasons. As a result I’ve had to turn down lots of exciting international opportunities. It’s a hard thing to do, but it feels like the right thing for me. For a long time in developed countries, it’s been aspirational to travel by plane for work but I think this is elitist and unsustainable. I’d love to hear more artists and designers discussing these issues and putting forward alternative ways of working.

Can you tell us about your record label, Blackford Hill and how that came about?

The Blackford Hill record label was started with my friend Simon Lewin who also runs St Judes (an online gallery that represents some great painters and printmakers). I’d contributed to one of the amazing Random Spectacular printed journals Simon produced. We became friends due to our shared interests in graphic design, printmaking, record sleeve art and music. Simon used to run an electronica label in the ‘90s called Fused and Bruised and I had an inkling that he’d be up for releasing some more music.

We started the label as a way to share projects made by our friends. Most of the releases are connected to, or inspired by, a sense of place. I’ve designed album covers ever since I was a kid. I remember spending hours making elaborate folding sleeves for cassettes and I used to daydream about getting to do it for a living. So it’s a total joy to get to work on the design of the label with Simon.

You recently launched the album, 'Ash Grey And The Gull Glides On' with composer Andrew Wasylyk. What drives this ongoing collaboration?

I first met Andrew about six or seven years ago – not long after I moved to Dundee when I was teaching at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design. Andrew asked me if I’d be up for making a music video for him, which quickly developed into me providing live projections for the concerts he performs with an incredible eight-piece ensemble. In 2019 I asked Andrew if he’d be up for making some music and we gradually pieced an album together. I think our collaboration is driven by a shared playfulness, curiosity and a willingness to experiment.

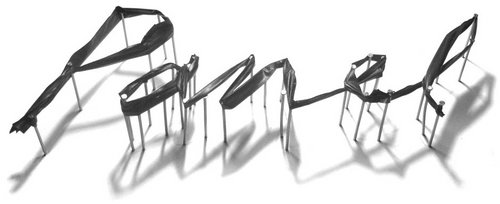

Tommy Perman

Born in 1980, Edinburgh, Scotland

Tommy Perman is an artist, designer and musician who works in a variety of media including visual art, performance, sound and music. He has a particular interest in combining new digital technologies with traditional techniques and materials and co-runs the record label Blackford Hill with Simon Lewin.

Between 2002 – 2013 Tommy was a member of the artist collective / band FOUND. As part of FOUND, Tommy has released numerous records and co-created a collection of weird and wonderful interactive sound installations including: Cybraphon which is now part of the permanent collection in the National Museum of Scotland.

Recent music releases include Music for the Moon and the Trees (2022, Blackford Hill) Sing the Gloaming (2020, Blackford Hill), Emergent Slow Arcs (2019, Fire Records) and Positive Interactions (2021) – a self-released album made entirely from happy sounds that can be purchased with a happy message.