Conversation / Fiona Jardine

Fiona Jardine discusses identity, style, fiction and a set of Look Book photographs found in the store room of iconic textile factory Barrie Knitwear.

November 2020

In 2013, for Glasgow’s Merchant City Festival, Panel presented Barrie Girls, an exhibition created in collaboration with graphic designers Sophie Dyer and Maeve Redmond, and artist Fiona Jardine.

Barrie Girls took its inspiration from a set of historical lookbook photographs loaned from the store rooms of Barrie Knitwear, a manufacturer of luxury cashmere based in the Scottish Borders. In the photographs, garment by garment, two unknown women model for the latest season of Barrie’s collection against a series of undefined backdrops within the factory and its grounds.

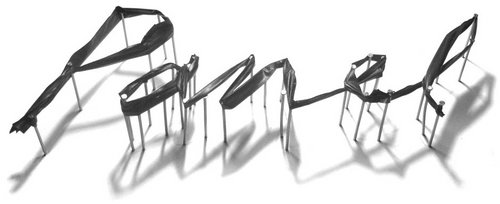

By re-examining and expanding potential narratives for the photographs, Dyer, Redmond and Jardine combined the collection with new graphic and written works to create a series of prints and texts. Ceci n’est pas une foto is the accompanying booklet to the Barrie Girls prints, containing a series of six short texts written by Jardine. Within the texts, historical and anecdotal narratives are interwoven to present an alternative snapshot of the Scottish Borders textile industry of the sixties. The names of people, places and consumable goods are conflated with the common advertising styles of the era as speculative scenarios, involving the two lookbook models, are presented.

Fiona, can you first of all tell us about the title of the text, Ceci n’est pas une foto?

It’s an allusion to Magritte’s famous painting of a smoking pipe, which is accompanied by the legend ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe’. In my mind, it has become conflated with ‘This is not just a [grocery], this is an M&S [grocery]’. Google tells me the original campaign ran between 2004 and 2007, which is at odds with the timeframe for Barrie Girls. It is a campaign that has never died. I go around thinking it all the time – ‘This is not just… this is…’. When I was looking at the photographs for the first time, I was thinking ‘These are not just photographs…’. You can complete that sentence with ‘…they are Barrie Knitwear photographs’ but for me, it opened onto a more ambient meditation on who the ‘girls’ were or could be. The photographs are ever so slight – in-house images for the sweaters Barrie were producing, divorced from any immediate information regarding price, style, date etc. Responding to your question, I looked up Magritte’s painting which appears to be titled ‘The Treachery of Images’. If I ever knew that, I forgot it, but it’s a great title. Very apt, in retrospect.

The booklet, which was commissioned as part of an exhibition of poster and text works by graphic designers Sophie Dyer and Maeve Redmond, is comprised of six stylistically different texts – what was your thinking behind this?

The photographs were introduced to me conversationally by Lucy and Catriona, Maeve and Sophie, so they were already attached to the stories they told about discovering them on location in Hawick.1 Hawick is one of those names that isn’t spoken as it is reads: you say ‘Hoik’. And it’s a place, surrounded by hills and moors, that takes a bit of getting to even if you have a car, and even if you live fairly locally. Beyond that, I didn’t know much about the photographs, I wasn’t physically in the archive ever, or pursuing an academic project, so I felt that my research could be, in those terms, illegitimate; that I could gather material I could work with – references, clichés, slogans, facts – intuitively, autobiographically, in a cascade of information, sometimes spurious. My aim was to craft this material into self-sufficient phrases, sentences and paragraphs and pass them on just as suggestions. I looked at the conjunction between knitwear and underwear; at the tropes used to promote Scottish textiles; at specific advertising campaigns, at the role of amateurs and affective labour in modelling. And I thought I should include references to the Borders as I think about them now, all these years after leaving, in terms of litanies and names. In lookbooks, the names of places, patterns, colours and people become substitutes for each other, they are interchangeable at that level. I thought I would string things together by writing with the notions of absurdity, disjuncture, familiarity and fact acting as stylistic devices to organise stuff for me in the absence of an immediate narrative.

Your texts within Ceci n’est pas une foto create historical fictions for a series of un-named women and introduce the idea of the ‘girl-next-door type’. Can you tell us more about why the photographs provided such a rich starting point for this kind of exploration?

First off, they reminded me of relatives. My aunts and great aunts, my granny and my ‘died’ granny, were known to me largely, and sometimes wholly, through photographs. With the younger ones, who were young in the sixties, there was quite a bit of posing in jumpers on country walks or picnics by rivers, almost replicating the images for the knitwear patterns they’d used. I think there is a sequence of one aunt on a tour round Scotland in a Beetle, posing in every picturesque lay-by. Another aunt I only know through a portrait she painted of an uncle. Half of my family have lived in the Borders for as long as anyone can remember, so I share the location with Barrie and the people they brought off the factory floor to model for them. It is actually feasible they could be relatives. They were amateur models and there is a glamour, a bit of romance, attached to being selected in that way. Growing up, I was romantically attached to the idea of being a Borderer, and maybe I still am. By casting the women in the pictures as relatives, I was also trying to bring them in from anonymity and in this way, the project touched upon one of my constant interests: I think a lot about how names are achieved and what names are worth. The relative ease with which you gain a name, or can be severed from it; the ways you are written into (and out of) discourse and memory, these literally describe the process of your entitlement, your privilege.

Your introductory text in The Persistence of Type*, ‘Caledonian Girls: A Picturesque’, reintroduces us to the Barrie Girls. How do you see these texts connecting to each other?

The Persistence of Type was a project that developed out of the excess of Barrie Girls. As a group, Lucy, Catriona, Maeve, Sophie and I felt that there were a lot of ideas, both formal and contextual, that we couldn’t give time or space to in Barrie Girls. Our research was the continuation of a conversation and conversation is good to centre in research. Ideas began to coalesce around the double meaning of ‘type’ as a kind of person, and ‘type’ as a graphic concern: we thought about the affective performance of fonts and the affective performance expected of people working in certain glamourous jobs as models, air hostesses or brand ambassadors, and the possible correlations between the two. There was also a parallel to Muriel Spark’s enjoyment of the double meanings of ‘type’ in her work – she thinks of herself ‘typing’ when she creates characters who emerge simultaneously with the manual act of using a typewriter. To me, the famous Tennent’s ‘Lager Lovelies’ were like the Barrie Girls with more position and purchase, credited with their name on behalf of the brand. The amateur girl-next-door is becoming the professional girl-next-door, and here there is the strategic use of names – Penny, Marie, Heather - to generate faux-intimacy. Looking at a the chronological range of Tennent’s pictorial lager cans, it surprised me to discover that the image of the first Lager Lovely, Ann, directly replaced postcard beauty spots and landmarks - the idiom is identical. It made perfect sense: the Lager Lovelies were a new picturesque.

The Barrie Girls are envisaged as part of a set, much like the Tennent’s ‘Lager Lovelies’ or the women that feature in the National Airline ‘Fly Me’ campaigns. Can you say a little about this advertising strategy and how it feeds into your own concept of the Barrie Girls?

Muriel Spark, again, took possession of the idea of a ‘set’ definitively in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. You can see the operation of the differentials that stand in for fully formed subjectivities right across commercial culture, and Spark used that as a creative device. So, in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Eunice Gardiner, who was ‘famous for gymnastics’ is, in one reading, an equivalent to Sporty Spice. Spark was directly appropriating an advertising slogan used by Darlings of Edinburgh, a department store, when she used this phrase, ‘Famous for’. You can see the strategy of the set being employed in the Lager Lovelies, British Caledonia’s ‘Caledonia Girls’ and in the National Airline ‘Fly Me’ campaign, whereby women exist as a palette of empirical options. There is an essay by James Krasner, ‘One of a long row only’: Sexual Selection and the Male Gaze in Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles, which discusses Hardy’s construction of Tess as the ‘best’ of a self-similar group – the one with the rosiest cheeks – and I find that very instructive here. As a counterpoint, I have in my head a line from Laura Branigan’s version of Gloria: ‘Gloria, I think they’ve got your number / I think they’ve got the alias / That you’ve been living under / You don’t have to answer / Leave them hanging on the line / Calling Gloria’. Good to think that under our aliases, our anonymities, we might be Glory…

Fiona Jardine trained in Drawing and Painting at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design in Dundee before undertaking an MFA at Glasgow School of Art in the early 2000s. Her PhD research in the Social and Critical Theory cluster at the University of Wolverhampton was concerned with the functioning of artists’ signatures. She is interested in theories of authenticity and authorship in art and textile histories. She was born in Galashiels and teaches in Design History & Theory at Glasgow School of Art.

Interview by Laura Richmond

* The Persistence of Type was a newspaper published for an exhibition of the same name at Tramway in 2015.

Buy Ceci n’est pas une foto here.

Access The Persistence of Type I, II and III from our Panel projects page here.