Conversation / Kirsten Carter McKee

Kirsten Carter McKee chats about Calton Hill's unique perspective over Edinburgh and place within Scotland's history.

February 2020

In 2018, Panel presented a collection of products in partnership with Collective’s new retail space, Collective Matter.

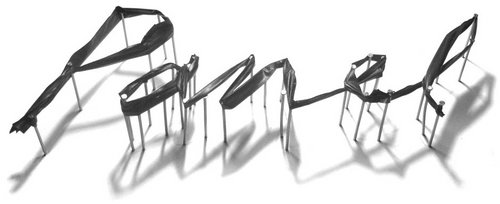

Souvenirs of Calton Hill are created by designers and artists in close collaboration with manufacturers and makers across the UK and Europe. Artists Rachel Adams, Mick Peter, and Katie Schwab; designer Katy West and photographer Alan Dimmick have designed the collection, each working with specially selected makers and manufacturers. Rachel Adams with Edinburgh-based jeweller Elizabeth Jane Campbell and Glasgow company Flux Laser Studio; Mick Peter with master weavers Alex Begg & Company in Ayr; Katie Schwab with Dundonian waxed cotton suppliers Halley Stevensons and Coatbridge-based garment makers Greenhill Clothing; Katy West with producers in Stoke-on-Trent and Alan Dimmick with Danish company Flensted Mobiles.

The resulting souvenirs encompass a range of disciplines and each product – in both form and production – is a new departure for its creator. Together they propose a series of uncommon products that invite visitors to consider Calton Hill through the lens of astronomy, timekeeping, trade, architecture and making. In this way, they speak to the history of Calton Hill and to Collective as a new kind of city observatory for Edinburgh, with contemporary art at its heart.

On Saturday 15 June 2019, Panel co-ran the Collective Matter shop on Calton Hill to launch Souvenirs of Calton Hill and we invited Kirsten Carter McKee, an architectural historian and cultural landscape specialist, to lead a tour of the hill to uncover some of the stories and inspirations behind their making.

Kirsten, your book Calton Hill and the plans for Edinburgh’s Third New Town considers in depth the history of this iconic place – and your wider research explores the social histories that have defined Calton Hill as a site of leisure, industry and protest. Why is the hill so central to the identity of Edinburgh’s citizens?

I think there are a number of answers to that. Visually within the urban realm, Calton Hill is very prominent from quite a number of different points within the city. I think the fact that it is an open public space makes it a very good place to gather. I also think that its lack of true ownership – despite development in the 19th century that really tried to take over the hill as a landscape of empire associated with the neoclassical new town – means that its proximity and its relationship to the old town and the working class of the city never disappears.

So, what you have is this site that anyone can access, that’s visually prominent and that everyone feels a strong sense of personal ownership over. I also think that the history of Scotland, and Edinburgh’s role in that history of cultural and political consciousness over the last 300 years, has really been played out on the hill and that’s something that I find particularly interesting. You can chart this through architectural forms and landscape design: Scotland’s own dialogue with itself as a nation, both within its own cultural context and as part of Britain.

We saw the Scottish Office being set up next to the hill, the Royal High School being promoted as a possible parliament building in anticipation for the 1979 push towards devolution and the subsequent protest and vigil for a Scottish parliament on the hill. Within the evolution of Scotland’s broader identity, Calton Hill contributes in a powerful way.

How did the Souvenirs of Calton Hill and their historical connections interact with the way you guided people around the hill?

I was really struck with how each of the artists responded to different facets of the hill and I wanted to draw out the particular narratives that they’d picked up on and build around them. Some examples are the social context of the washerwomen and the drying sheets, the context of astronomy, science, the enlightenment and navigation and its connections to Leith. Katy West’s jars opened up dialogue about how Leith trades were funded through slavery, connecting to broader discussion about Scotland and empire. All of these elements can be read from the hill.

My guided tour took the ideas that each artist explored as a starting point to bigger stories. I thought it really showed the quality of the site, that each of the artists had such a diverse kind of approach and had picked out different stories connected to the hill.

This project has prompted us to think about the panoramic view of Calton hill as an iconic souvenir in itself – How does this speak to your research of the hill?

I think that Calton Hill’s panorama is physically and intellectually central to how I have approached my research. When you look at that panorama, you have this consciousness of the urban and the rural side by side. The building design on the hill in the 19th century picked up on this, bolstering the notion of the picturesque that evolved in the late 18th and early 19th century. So, there’s that kind of standard exploration of 19th century picturesque architectural design but then also this consciousness of Calton Hill being this sentinel for Scotland.

Calton Hill offers views of the sea, drawing the city itself into a bigger, global story. On the hill, looking to the north, you’re very conscious of the proximity to Leith, the Firth of Forth and beyond and to the south you have Arthur’s Seat and then the other Edinburgh Hills in the distance. Suddenly one starts to see this much broader context of the city and its functionality within itself and then towards the water, towards empire. So, for my research, that’s where I started from; that looking outwards.

What does the arrival of Collective within the Observatory complex signify to you and your research?

The arrival of Collective is such a positive influence. Calton Hill was considered to be a neglected and underappreciated space and now I’m struck by the number of people I see each time I visit, even on a relatively wet and windy day. It’s becoming more prominent in the consciousness and history of Edinburgh and these broader histories touched on by the Souvenirs of Calton Hill are so important to draw out as a part of that.

What are you working on at the moment?

My work re-explores our accepted history and considers neglected parts of our historical narrative in Edinburgh, how we read the influence of empire and the transatlantic slave network within what we see within the city’s urban realm. There is a way we tend to talk about history in connection to our urban environment and it’s very much a singular narrative - a specific perspective. I am interested in opening up discussion around women within urban environments, about representations of race within Scottish urban environments and also how LGBT history has been defined through the urban realm. Obviously, these histories are just as valid as contributions to our understanding of contemporary society, but currently they are so under-represented within our academic thinking.

Do you have a favourite fact about the hill?

My favourite story was told to me by the historian Charles McKean, professor of History at the University of Dundee, about the Elgin, or Parthenon, Marbles. His story goes that when Lord Elgin first brought the stolen marbles back to Britain, he made attempts in vain to sell them to the British Government, but the price wasn’t high enough. Upon bringing them back to his home in Fife, he began conversations with the architect Charles Cockrell about including them within Edinburgh’s proposed monument to the Napoleonic Wars.

Amongst proposals for triumphal arches and gothic churches, Elgin championed Cockrell as lead architect alongside William Playfair. Known for his neo-classical work, Cockrell had completed extensive studies on the Parthenon, and Elgin pushed the idea that his stolen marbles could be included within a Cockrell designed national monument. This of course never happened and the monument (now known locally as ‘Edinburgh’s Disgrace’), prominently sited on Calton Hill, stands unfinished due to lack of funds when building ceased in 1829.

Incidentally Elgin also had casts made of the marbles, which were gifted to Edinburgh College of Art. In 1907, when the College’s permanent building was designed, the sculpture court was drawn to the exact dimensions of the Parthenon in order to house the casts. It’s a really nice narrative that takes you into the present day. In my time, social events were held in the sculpture court surrounded by these casts and free-standing sculptures. I remember going to club nights where there’d be sculptures wrapped in feather boas and now, we’ve found out that these are really priceless artefacts! How prominent they are, in not just the design of the art school and also in the iconic structures of Calton Hill, but also as totems, which illustrate Scotland’s role in Britain’s imperial understanding of its place in the world.

Kirsten Carter McKee is an architectural historian and cultural landscape specialist. She has a PhD from the University of Edinburgh and has worked for a number of organisations as an archaeologist, historic buildings specialist and heritage consultant. She is currently a research and teaching fellow in architectural history and conservation at the University of Edinburgh. Kirsten’s recent publication, Calton Hill and the plans for Edinburgh’s Third New Town was published in 2018.

Interview by Laura Richmond.

Read more about Souvenirs of Calton Hill here.