Conversation / Rob Kennedy

Rob Kennedy on his video work 'What are you driving at?', the hold of cinemagazines, advertising, factory automation and the failing grip of twentieth century British propaganda.

May 2021

Produced by the Central Office of Information (COI) to showcase British manufacturing and promote the ethos of the British Commonwealth, the Roundabout cinemagazine series offered a mix of official opening ceremonies and factory production lines, and bore witness to a Britain projected exclusively to cinema audiences in Asia throughout the 1960s and ‘70s.

Co-curated by Panel, with Annette Lux and Steven Cairns, and organised in partnership with the British Film Institute Archive, House Style presented a series of short film commissions by designer Hilda Hellström, writer Travis Jeppesen, artist Rob Kennedy and musician and composer Daniel Padden, exhibited at Tramway in 2013. Reconsidering and repositioning stories from the Roundabout series, the films set out to explore the ways in which cultural identity, status and style can be understood through design, industry and image making.

Cinemagazines first appeared in British cinemas during the early half of the 20th century, proliferating after the Second World War with many series broadcast into the late 1960s and early 1970s. Predominantly produced by the COI, they were designed to promote Britain as a national brand, emphasising its pioneering industries, trade and cultural activities to overseas audiences including those of the Commonwealth, the Middle East and the USA among others. The Technicolor series Roundabout (1962-74), is an example of such ‘soft propaganda’, and working with a number of clips selected for their subject matter, as well as their visual and contextual appeal, the commissioned films present a unique and varied experimental reading of the archival source footage.

Rob Kennedy’s What are you driving at? explores aspects of power within the promotional feature, including expressions of technical innovation, cultural composition and image construction in contemporary media. With these relationships in mind, sound and image sampled from contemporary television and internet sources interplay with footage from the Roundabout series. Through the seamless overlaying of industrialised processes, human interventions and fluctuating engine sounds, the film looks at changing modes of promotion and how human connections to production and industry have shifted since the apex of the cinemagazine.

What drew you to these three particular Roundabout films and what connections did you draw between them?

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Roundabout cinemagazine series is how each programme edits together very diverse subject matter and locations into a strange, seamless whole. The films all promote an underlying poetic abstract even whilst attempting to narrate a cohesive storyline. Showcasing industrial skills and techniques was the pre-requisite and it was up to the producers and editors to corral these into the narrative of British power that was to be presented. I was intrigued by this very modern editing aspect, which is closer in output to late-twentieth century pop video production than it is to mid-century industrial promotional f ilms. There is a real wow factor about the Roundabout series; the fact it was produced in Technicolor and only for cinema audiences, situated it in the realm of high production values and epic cinema vision at the time, meaning that it wasn’t just the content of the films that was deemed to be important. There seems to be a great understanding of the power of cinematic language and of how effective this type of communication could be in the public entertainment realm. The three films I chose were Dress Show and Make-up from issue No.5 and Plastics from issue No.12. There were a lot of interweaving links between these three films; the mixing of chemical elements to create lipstick in one film and vac-formed plastics in another don’t look too different when you see them side by side. Similarly, the expressionless movement of the make-up models share similar rhythms with some of the mechanised processes, and the shiny new products in turn perform in a similar way to the models posing for the camera. This melding of forms and motion allowed me to extend the abstractions further by discarding the narrative of the original soundtracks, which I think intensifies the material fluidity and amalgamation of forms.

What are you driving at? is characterised by sounds of a car as it starts up, accelerates and decelerates, creating stability and agitation in equal measure. How integral was the inclusion of this particular type of sound in creating the film?

Visually, I was trying to get all elements to push and pull at each other, emphasising the malleability of all these materials, whether human, machine, liquid, plastic, etc., and show the shifting relationships that form and recede between them all. The soundtrack needed to do something similar and yet carry some kind of narrative drive that would give an overall shape and drama to the video. I think part of the inspiration for it came from a similar idea of abstraction that you get in car adverts whereby directors can’t just film a car anymore – they have to take the audience on an emotional journey through the workings of the machine, or present the body of the machine as a physical and sensual extension of the owner, or map the psychological makeup of the idealised driver to show how the machine personifies their desires. Again, it’s all about malleability. The car engine part of the soundtrack is taken directly from an original advert for an Audi R8 V10 sports car. The actual advert is one-minute long, so I have stretched, repeated, filtered, and processed the original as well as adding additional supporting engine sounds, treating it as just another material to be shaped, mixed and coerced. The car engine is bookended by the sound of a small pharmaceutical machine repetitively producing a supply of pills. There is a gentleness, perhaps even a comforting aspect of this sound, that then gets drowned by the sheer force of the car engine but then calms everything down again when it returns at the end. For me, the manipulated car sound subtly shifts from being completely mechanical and chemical, to something quite animal and even human with the deceleration. There is something about rhythm, pulse, like breathing that seems to underscore how the sounds layer over each other. I don’t remember this as something I set out to do, more that it was the result of playing with those sounds and feeling through how they interacted with the images.

The exchange you present between the manufacturing of beauty products and automation in the plastics industry is really fascinating. As clips of factory assembly lines and production are presented it can take a moment for the viewer to register what product they are observing in the making. What are your thoughts on the relationship between these two industries?

This is one of things that stood out for me at the beginning of the project. After having stripped away the narration of the original films, all the industrial processes began to look very similar. In effect, the basics I suppose are really the same – various chemical and physical processes that turn one substance into another. It’s just the purpose that’s different. In the ‘60s, when these original films were made, the processes that we see were obviously at the cutting edge of manufacturing. This is why the films were produced – in order to advertise British innovation around the globe. Although now these processes look very hands-on and outdated, there is something otherworldly about how they have been filmed, particularly in the use of Technicolor. The majority of promotional filmmaking at the time would have been 16mm black & white, so to produce Technicolor 35mm films about such pragmatic subjects seems like a huge leap, both in budget and in intention. There is something almost alchemical about how amazingly saturated the coloured pigments appear and the incredible detail shown in the various fabrics, powders, and plastics produced. Today we are so used to the liquid flow of material in HD adverts for Sony TVs, iPhones, computer chips and cars, that we almost don’t notice this abstraction of the product. Seeing the direct connection between the human, machine and chemical components in these films brings to life the fact that we are biologically connected to the ‘man-made’ things and processes that we invent and produce. Product advertising has developed in such a way that images of the product now feature as just a tiny part of the advert itself. The advert delivers an emotional narrative to create a tie between the consumer and the product. The psychological drama presented in the advert is what ties us to the product, rather than the quality or usefulness of the product itself. In this way the stories used to advertise things are often interchangeable and thus begin to look very much alike. In fact, with the sound down it often becomes difficult to know what is being advertised until the logo appears at the end and we log the relationship.

As the film develops the archival video footage is fused with scenes of modern-day factory and office environments. Can you say a little about your choice to integrate contemporary footage into the film?

Part of the reason behind my selection of these Roundabout films, was the human/machine relationships that drove their narratives. This point in British industrial history could be seen as the zenith of this relationship before the advent of new technologies and the dismantling of traditional industries that began in the following decade. Now, fifty years on, the UK’s relationship to manufacturing technology is so much more distant. Having fully embraced the rationale of the service industry there is only a limited hands-on understanding of how and where our manufactured goods are produced. This disconnect is further emphasised in the abstract way the products we consume are advertised to us, the transference of use value to desire and lifestyle choice. The modern clips of iPhones liquefying or the hi-speed blurring of plastic water bottle production were used to emphasise how ungraspable these manufacturing processes are now to the majority of the world’s population. The fusing of this contemporary material is to literally show how this understanding of physicality has, over time, slipped from our grasp.

Can you tell us how What are you driving at? interacts with aspects of power and cultural identity within British promotional features such as the Roundabout series, which were made for overseas audiences to promote British business and industry?

What I found fascinating about the original films was the malleable relationship between the image content and the political intent. The use of 35mm Technicolor and the abstraction of narrative must have appeared quite spectacular at the time in advertising such prosaic aspects of industry. The films share a similar ‘50s visual splendour with the likes of Hitchcock or Powell & Pressburger, whilst using quite abstract storytelling techniques that lend themselves to a more experimental mode of filmmaking, and yet, they are all wrapped up in this advertising cloak, promoting a dying imperial Britishness. This awkward but dynamic set of relationships gives the films their distinct character, something very modern and fluid yet steeped in tradition and power politics. The title What are you driving at?, whilst obviously being a pun in regard to the soundtrack, is a question both of communication and of power. The phrase ‘What are you driving at?’ is a question to decipher the underlying, hidden or obscured meaning of a thought process, but it also asks what it is that is being targeted. I was thinking about how the power of the Roundabout films is embedded in the technology and industry used to produce them as much as it is in the content they narrate, the industrial capacity of the filmmaking process accentuating the colonial power relationships that the narratives are seeking to confirm.

How were you interested in shifting the narrative of the Roundabout series?

The whole series of Roundabout films are a fascinating archive of a specific point in British commercial and cultural history. There is a glamour and power to them that seeks to mask the ongoing effects of post-war recovery with traditional British bombast. They are infused with a strange parochialism, unaware or blinkered as to Britain’s changing relationships with the rest of the world. The second half of the twentieth century saw the decimation of British manufacturing, which has produced an import culture where the majority of consumer products are manifested through unseen processes in far-off lands, meaning our hands no longer get dirty, and we have an arms-length understanding of how the world is being produced around us. What are you driving at? fuses these archive films with contemporary advertising images in an attempt at visualising this melting of control, this exchange from physical relationship to evanescent need.

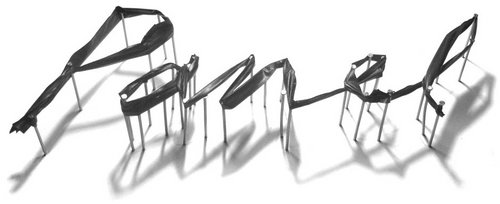

Rob Kennedy is an artist who lives and works in Glasgow. His work in sculpture, video and live events is concerned with the physical manipulation of materials, language and time, using the detritus found in our physical and economic environments to pose questions about social and political relationships. He often collaborates with other artists and non artists in order to debate ideas of authorship, responsibility and creative autonomy.

Watch What are you driving at? by Rob Kennedy here.

Watch a short interview with Rob Kennedy about acts of dis play here.

Interview by Laura Richmond