Conversation / Sally Hackett

Artist Sally Hackett on connecting with Ester Krumbachová through A Weakness For Raisins and the direction her work has taken during lockdown.

August 2020

Ester Krumbachová was a key figure in Czech New Wave cinema during the 1960s, contributing significantly as a costume designer, stage designer, scriptwriter, author and director. After the 1968 Prague Spring, she was one of many Czech artists effectively silenced and nonofficially banned from Barrandov Film Studios until 1989.

Krumbachová has returned to public consciousness recently as her papers, artwork, photography and clothes were donated to create an archive, overseen by curators Edith Jeřábková and Zuzana Blochová (ARE Events). The archive is beginning to shed light on Krumbachová’s time, with many topics – agency, magic, materialism, gender, feminism, the interconnected nature of reality, and sensory forms of knowledge – remaining relevant today.

Focusing upon a series of pen drawings by Ester Krumbachová and costume from the Barrandov Film Studios Costume and Props Collection, Panel, through invitation from ARE Events, commissioned new work by Sally Hackett and France-Lise McGurn that made reference to friendship, power, authorship, alchemy and style. The work was presented as an installation within A Weakness for Raisins, an exhibition co-curated by ARE Events, CCA and Panel, alongside a film season dedicated to Krumbachová’s work at CCA in 2018.

Sally’s response to the archive resulted in a deeply reflective and playful collection of work centring around instances of group interaction. Through exhibition display, her work extended out to include visitors of the exhibition, inviting them in, through a series of perspex plinths and mirrored shelves, to involve themselves in the trials and conflicts of her protagonists.

Sally, the work you created was in response to the life and work of Ester Krumbachová. What elements of Ester were you most drawn to?

One of the main things I love about Ester is the complexity of emotion she gets across in her work. Her work is so eruptive - a volcano of female misbehaviour and destruction - setting things on fire, squashing up food and laughing at men. Yet her work is so tender and emotional at the same time. She manages to convey fury, intensity and vulnerability all at once. It seems to me that she approached everything she did with bags of humour, openness and tenderness. Yet also with a fierceness of intention. When invited to universities to deliver talks, instead of delivering a traditional formal lecture, Ester would write her talk in the form of a letter, addressing her audience directly and including personal anecdotes and commentary. I really love this unguarded and humorous approach to academic worlds. She also wrote personal letters. Her letter to her cats, where she describes her devotion to them and sadness at them dying, was one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever read. Her drawings were so amazing! Holding so much empathy and expression in a line. Looking at some of them totally broke my heart. Overall her work felt encouraging - it felt like she was taking your hand, but not in a cutesy way. She was taking your hand, dragging you and running to the nearest bar.

Both yourself and France-Lise McGurn were invited to consider Krumbachová’s work through the lens of two key films, 'The Murder of Mr Devil’ and ‘Daisies’. In thinking specifically about their styling and art direction, how did you choose to work with the ideas, including exploration of relationship dynamics and subversion of the male gaze, that the films presented?

Both of the films had a strong sense of mischief, but a darkened mischief fuelled by something more serious, fuelled by rage. The styling and art direction of both films also took this on, appearing visually in glowing plates of food, bursting flowers and delicate butterflies. These pretty objects are always interrupted with acts of destruction - cut up slowly with scissors, or smashed to the ground with a freeing recklessness. In ‘The Murder of Mr Devil’, there is a bit where the central male character starts eating the furniture. Huge chunks are gnawed from a previously elegant table leg.

I wanted to take on this stance of the ‘interrupter’ in my work for the show. A figure entering and interrupting typically ‘nice’ scenes. In ‘Daisies’, there are scenes throughout where one of the main characters directly sabotages the other’s potential ‘romantic’ encounters with terrible men in solidarity. Three of my pieces within the show engaged with this idea, materialising as the concept of ‘the third wheel’. In these sculptures, romantic encounters are depicted (people kissing or having sex) alongside a disapproving onlooker. The third wheel. The third character intends to dominate the work. They possess the power. Friendship is intended to be at the core of these pieces instead of romantic concern. Friendship over romance.

My piece ‘couples arguing’ was directly inspired by Ester’s film ‘The Murder of Mr Devil’, in which the female central character has a tiresome relationship with a hysterical man who spends the duration of the film crying, arguing and eating excessively. ‘couples arguing’ is a set of five figurative sculptures, each composed of heads and hands, depicting five expressive scenes of couples arguing. Each couple are mounted on a shelf made of mirrored perspex, allowing the viewer to literally see themselves in the work. In this instance the viewer is intended to be the third wheel, the interrupter of the image, the friend, the empathiser. I worked directly from stills from the film, looking at the theatricality of the central couple’s body language. I think watching couples’ interactions in public is like a sort of theatre. Break-ups on park benches are so sad but so fascinating.

Your sculptures are often personal and humorous reflections on a variety of interpersonal relationships and exchanges. But this time you took an archival approach. Can you say a little about working in this different way?

I feel like it worked quite naturally because I felt a real affinity to Ester’s work. I looked first for similarities in our work, or things about Ester that sparked my interest, and these weren’t hard to find. It wasn’t too different to my usual process in that I often look at a lot of images and other sources of inspiration before starting a piece of work. The special thing about working in this way was having a connection to another person. The making of the work was like having a relationship with someone who’s no longer physically there and who you haven’t physically met, which feels like a very unique experience. Through looking at Ester’s work, and making in response to it, I felt really connected to her. I felt her spirit guiding me around like a cool new auntie. Ester felt like a ghostly mentor to me.

Your figures are often accompanied by a narrative voice. How central is language to your work?

Words and phrases inspire me a lot. I make a lot of little one-liners in my iPhone notes and weirdly often come up with a title for something before I’ve made the sculpture. I used to feel like I wasn’t ‘well read’ enough for language to be a big part of my work but it’s crept in naturally and I like having it there - and now I’ve realised that mindset was very problematic and sad! The inspiration for my text mostly comes from conversations with friends, things I hear in public or things people say on TV. I’m also extremely inspired by memes and the hand-holding of text and image to compose things which are frivolous and wildly intelligent at the same time. One can’t work without the other. In this way, a title of a work can be everything, but if no one is going to read it, sometimes it’s best to just paint it right on the front.

You were working between London and Glasgow for this exhibition. Did this affect the way you went about making the work for the exhibition?

Not really! I often make my work as lots of separate ceramics pieces which I then collage together, so this worked well for shipping the work - there were lots of ceramic body parts wrapped in boxes! It did also mean that I got to drive in a van from London to Glasgow with my friend Hannah with the work, screaming up the motorway singing. In itself this was quite a beautiful journey of friendship that felt very fitting and apt for the exhibition. It could have been a scene from ‘Daisies’, the 2018 version.

We have loved seeing your Instagram feed showing works made at home over the past few months. The images are so brilliant at reflecting the mood of lockdown, through the materials you have used and their accompanying captions. What has creating work been like for you during this period?

Making work during this time has been really strange! At times it has felt silly and insignificant but simultaneously, completely essential to maintain some level of mental grounding.I’ve felt really connected to my childhood self during lockdown. I think because it’s the first time I’ve spent a prolonged period of time at home and outside. Spending all of this time with the same household objects made them come to life for me and I started seeing them as live entities in themselves - a garlic husk became a swan and a tissue popping out of a tissue box became a wave in the sea. I’ve really enjoyed animating these objects in analogue ways by taking them outside and filming them blowing around in the wind. This state of imagination reminds me of being a child - when I thought my cereal was alive and my toys had feelings. I’ve spent a lot of time staring melancholically into space but then noticing so much beauty in little pieces of tin foil and bubble wrap. Glimmers of shininess in veils of sadness and worry.

Going on long walks around the same streets every day, I’ve seen things like dog poo bags squashed into the street with the top ties flapping around like a fishes tail. Strangely enough it is moments like these that have inspired me the most.

Alongside making my own work, I’ve been composing art workshops for kids. Due to the workshops happening remotely it’s essential that the materials list is easy to find and accessible. This has led me to activities like making furniture out of gravel. This play with materials has definitely made me more creative.

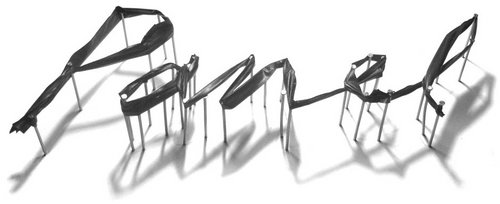

Sally Hackett is an artist and educator working in Glasgow. Sally has collaborated on projects with a wide range of organisations such as CCA, Hospitalf ield, Glasgow Sculpture Studios, Panel, Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop and Glasgow Women’s Library. Recent Commissions include A Weakness for Raisins’ CCA, Glasgow (2018) ‘From Glasgow Women’s Library’ (2018) and ‘The Fountain of Youth’ Edinburgh Art Festival (2016).

Interview by Laura Richmond

Read Sally Hackett and France-Lise McGurn’s letters to Ester here.